Variadic Functions in C

Variadic Functions in C

The word variadic tells us that there is some kind of change, or variation involved, the word variation in a function, means that we are dealing with an unknown number of arguments for a function.

We typically use a variadic function when we do not know the total number of arguments that will be used for a function, one singule function could potentially have `n' number of arguments and it will contribute to the flexibility of the program that you are developing.

Actually, the concept of a variadic function is already used in several C's built-in functions, in printf, for example, when we want to print one or many numbers:

printf ("The one number: %d\n", one_number);

printf ("The first number %d, the second number %d.\n", one_number,

second_number);If you look at the `stdio.h' header, you can see that this function was implemented using variadic functions. If you need to do this yourself, the `stdarg.h' header file provides you with routines to write some of your own variadic functions.

Using a Variadic Function

A variadic function has two parts:

-

Mandatory Arguments: at least one argument is required, and is the first one listed, that order is very important, the mandatory argument CANNOT be at the end, for example.

-

Optional Arguments: These are listed after the mandatory arguments.

Continuing with the `printf' function example, the first paramter is mandatory, which is the format, and the optional part comes after and it could be different, depending on the situation you are in.

The common practise for the mandatory argument, is to have accept a number that will tell us how many arguments there are, for example, if we have a variadic function, we call it with 5 as its first argument, meaning we will pass 5 optional arguments to it.

Creating a Variadic Function

In order to create a variadic function, you have to understand how to reference the variable number of arguments used inside the function, you do not know how many there are and you cannot possibly give them names, you can solve this problem indirectly, through pointers.

The `stdarg.h' header provides you with routines that are implemented as macros, that will allow you to implement your own function with a variable number of arguments. The macros that you need to understand are:

-

va_list: This is used in situations in which we need to access optional parameters and it's an argument list, it represents a data object used to hold the parameters corresponding to the ellipsis part of the parameter list.

-

va_start: This macro is going to connect our argument list with some argument pointer, the list specified in `va_list' is the first argument, and the second argument is the last mandatory argument.

-

va_arg: This will fetch the current argument connected to the argument list, we would need to know the type of the argument that we are reading.

-

va_end: This is used when we would like to stop using the variable argument list.

-

va_copy: Is used in situations for which we need to save our current location.

Step 1

The first step to create a function with a variable number of arguments is, provide a function declaration using an ellipsis (three dots). The ellipsis indicates that a variable number of arguments may follow any number of fixed arguments, and remember that this function must have at least one fixed argument.

The following is a valid variadic function declaration:

void function (int number, ...);As you can see it has the first mandatory argument, and then the ellipsis. The following is also a valid variadic function declaration:

int function (const char *string, int n, ...);In that declaration, there are two mandatory arguments and then there's an ellipsis, telling the compiler that a variable number of arguments may follow.

And now, this declaration is invalid:

char function (char c1, ..., char c2);Because the ellipsis is not last in the declaration, the ellipsis CANNOT be in between other mandatory arguments.

Step 2

In the function definition, you have to create a `va_list' type variable and then, you initialise the variable to an argument list, you need to copy the argument list to the `va_list' using `va_start' as shown in the following snippet:

double

average (double v1, double v2, ...)

{

va_list arguments; // a pointer to the variable argument list

// More code goes here

va_start (parg, v2);

// more code?

}In that example we are declaring the variable `arguments' of type `va_list' and then we call `va_start' whith the va_list as first argument and we specify the last fixed parameter `v2' as the second argument, the reason why we call `va_start' is to point `arguments' to the first variable argument that is passed to the function when it's called, we still don't know what type of value this represents.

Step 3

Now, you can access the contents of the argument list using `va_arg', this macro takes two arguments: a type `va_list' variable and a type name, the first time it is called, it returns the first item in the list, the next time it's called, it returns the next items, and so on. The type argument specifies the type of the value returned - it has to match the specification.

Consider the following example:

double

a_function (int lim, ...)

{

va_list ap; // declare object to hold arguments

va_start (ap, lin);

double tic = va_arg (ap, double); // retrieve first argument

int toc = va_arg (ap, int);

}If the first argument is `10.0', the above code for `tic' works fine, if it is 10, the code may not work as the automatic conversion of double to int that works for assignment doesn't take place here.

Step 4

The last step is cleaning up. You should clean up by using the `va_end' macro as your last step, it's essential to tidy up loose ends left by the process. This macro takes a `va_list' variable as its argument and resets its pointer to NULL. If you omit this call, your program may not work properly, the variable might won't be usable unless you use `va_start' to reinitialise it.

This is how the final function would look like:

double

a_function (int lim, ...)

{

va_list ap; // declare object to hold arguments

va_start (ap, lin);

double tic = va_arg (ap, double); // retrieve first argument

int toc = va_arg (ap, int);

// Do something with tic and toc?

va_end (ap);

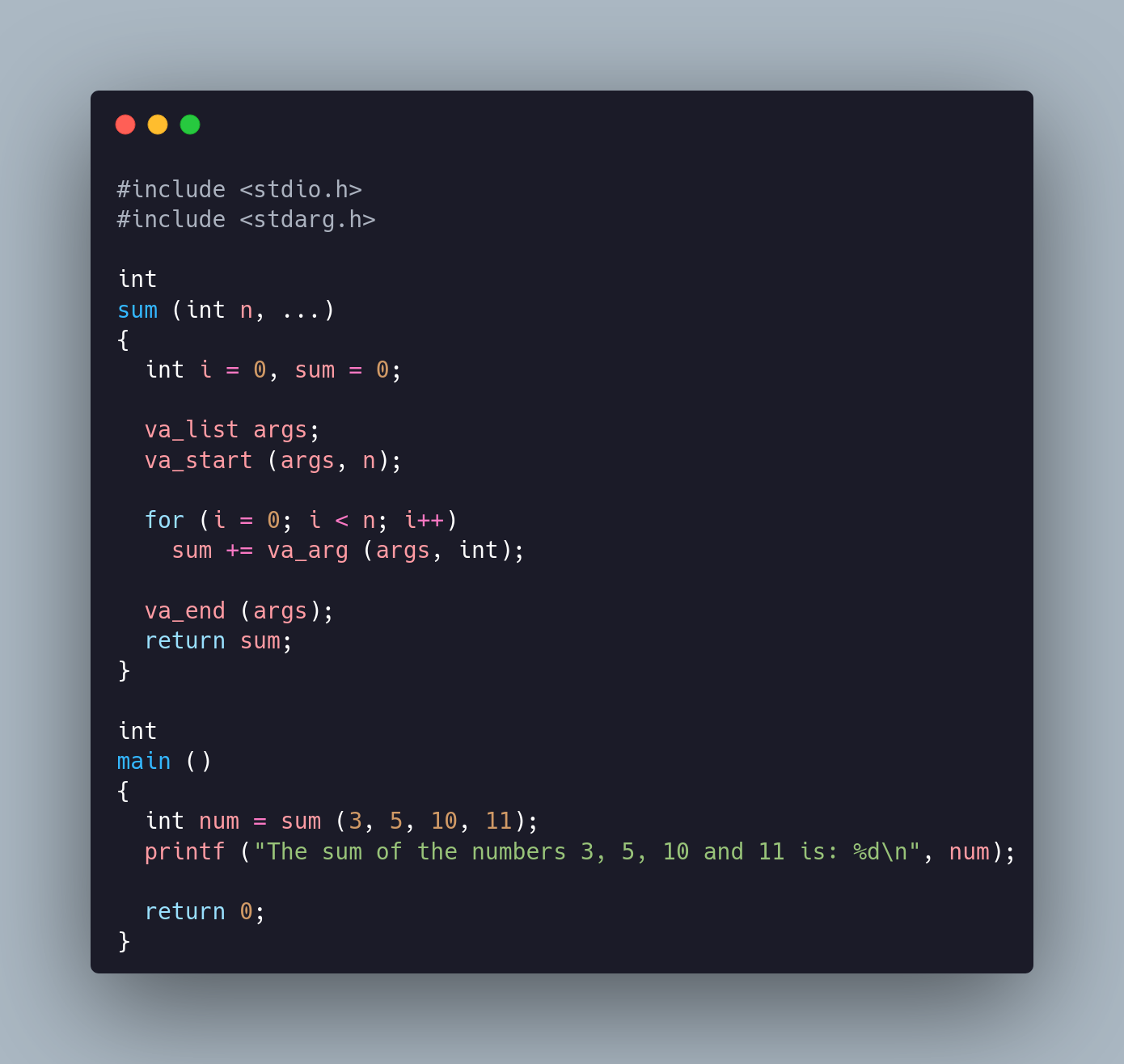

}A functional example

Consider this example:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdarg.h>

double average (double v1, double v2, ...);

int

main ()

{

double v1 = 10.5, v2 = 2.5;

int num1 = 6, num2 = 5;

long num3 = 12L, num4 = 20L;

printf ("Average = %.2lf\n", average (v1, 3.5, v2, 4.5, 0.0));

printf ("Average = %.2lf\n", average (1.0, 2.0f, 0.0));

printf ("Average = %.2lf\n", average ((double) num2, v2, (double) num1,

(double) num3, (double) num4));

return 0;

}

double

average (double v1, double v2, ...)

{

va_list args;

double sum = v1 + v2;

double value = 0.0;

int count = 2;

va_start (args, v2);

while ((value = va_arg (args, double)) != 0.0)

{

sum += value;

++count;

}

va_end (args);

return sum / count;

}And this would be the output of that program:

| Average | = | 5.25 |

| Average | = | 1.5 |

| Average | = | 8.42 |

Let's go through that code:

`average' is a function that, basically, calculates the average between two or more arguments, the first thing we did was to create a `va_list' variable called `args' and then we create another variable of type double called sum, whose value is the addition between the two mandatory arguments `v1' and `v2', we will accumulate the sum of all the arguments in the `sum' variable. The other variable we create `value' contains the value of the variable argument we are currently in, this is obtained through `va_arg', the count variable will just count the number of arguments and now, we start our variadic argument list, remember that it takes as arguments the va_list and the last mandatory argument of the function.

We have a while loop whose condition calls another function fom `stdarg.h' which returns the argument value we are currently in, and we are storing this value in the `value' variable and we are comparing this value with `0.0', if `value' is equals to `0.0' stop the execution of the loop. Inside the loop, we just have statements for adding the value to sum and incrementing count by one, finally, we are calling `va_end' to free our va_list and we are returning the division between sum and count.

In Summary

-

There must be at least one fixed parameter.

-

You have to call `va_start' to initialise the value of the variable argument list pointer in your function, this pointer must be declared as type of `va_list'.

-

There needs to be a mechanism to determine the type of each argument, either there can be a default type assumed or there can be a parameter that allows the argument type to be termined. For example, you could have an extra fixed argument in the `average' function that would have the value 0 if the variable arguments were double and 1 if they were long.

-

You must have a way to determine when the list of arguments is finished, for example, the last argument in the variable argument list could have a fixed value - this is called a sentinel value - or the first argument could specify the count of the number of arguments in total or in the variable part of the argument list.

-

You must call `va_end' before you exit a function with a variable number of arguments, if you don't, the function will not work properly.

va_copy

va_copy is a way to copy the arguments as `va_arg' doesn't provice a way to back up to previous arguments. It is possible that you may need to process a variable argument list more than once or to preserve a copy of the `va_list' variable.

va_copy takes two arguments the destination and the source va_list. This is a little example on how it would be used:

va_list arg;

va_list arg_copy;

va_copy (arg_copy, arg);That little snippet of code will copy the values of `arg' into `arg_copy' and now you could process `arg' and `arg_copy' independently to extract argument values `va_arg'.

It's important to note that the `va_copy' function will copy the va_list exactly as it is, if you have alreadey exected `va_arg' to extract argument values from the list before calling `va_copy', the resulting va_List will be in an identical state to the source va_list.

Don't use the same `va_list' variable as destination twice before calling `va_end' on it first, don't do this:

va_list arg;

va_list arg_copy;

va_copy (arg_copy, arg);

va_copy (arg_copy, another_valist);You'd have to call `va_end' for `arg_copy' first.