Recursion in C

Recursion

Before we specifically talk about recursion, let's talk about why we might need to use something like recursion. The programs we have curerntly discussed are generally structured as functions that call one another in a hierarchical manner. For some types of problems, it is useful to have functions call themselves, that's what a recursive function is, it's a function that calls itself either directly or indirectly.

Recursive functions can be effectively used to succinctly and efficiently solve problems, they are commonly used in applications in which the solution to a problem can be expressed in terms of successively applying the same solution to subsets of the problem.

You are unlikely to come across a need for recursion very often, it provides considerably simplification of the code needed to solve particular problems. It takes a great deal of practise writing recursive programs before the process will appear natural.

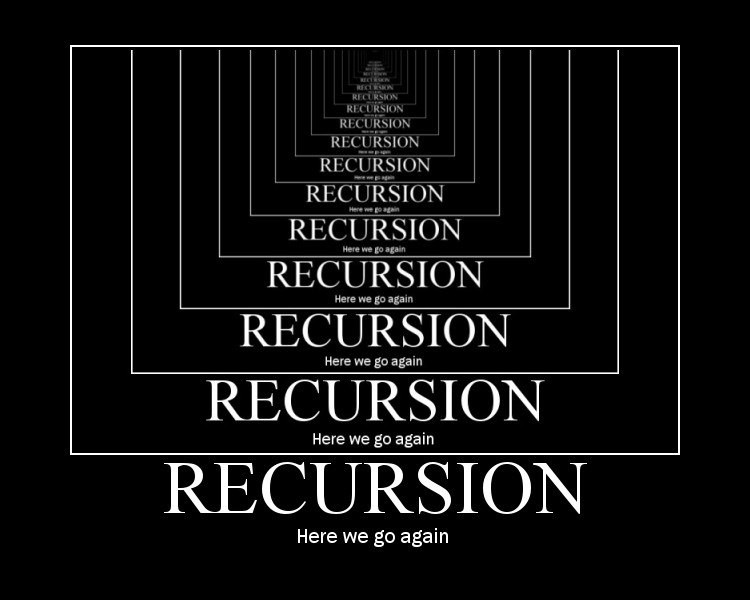

Recursion can be confusing and tricky at first, when a function calls itself, there's the immediate problem of ho the process stops, for example:

void

function ()

{

printf ("function called.\n");

function ();

}Calling that function would result in an indefinite number of lines of output, after executing the `printf' call, the function calls itself, there's no mechanism in the code that will stop hte process, this is similar as having an infinite loop.

A function that calls itself must contain a conditional test (base case) that terminates the recursion. Consider the following example:

int

factorial (int n)

{

if (n == 0) return 1;

return (n * factorial (n - 1));

}When a recursive function is called with a base case, the function simply returns a result, in that example, the recursion is at the bottom of the function n * factorial (n - 1) and our exit condition is the if (n == 0) return 1;

When the function is called with a more complex problem, the function divides the problem into two conceptual pieces: a piece that the function knows how to do and a slightly smaller version of the original problem. That's what recursion is about, breaking a problem into smaller chunks.

The recursion step can result in many more such recursive calls as the function keeps working on the smaller problem. For recursion to terminate, the sequence of smaller problems must converge on the base case, when the function recognises the case, the result is returned to the previous function call, a sequence of returns ensures all the way up the line until the original call of the function eventually returns the final result.

Recursive functions are most commonly illustrated by an example that calculates the factorial of a number, the factorial of a positive integer n, written `n!', is simply the product of successive integers 1 through n, the factorial of 0 is a special case and is defined equal to 1. For example:

5! = 5 * 4 * 3 * 2 * 1 = 120In the general case, the factorial of any positive integer n greater than zero is equal to n multiplied by the factorial of n - 1, that's why we did:

return (n * factorial (n - 1));In the factorial example above. It looks - expressed mathematically like this:

n! = n * (n - 1)!The expression of the value of n! in terms of the value of (n - 1)! is called a recursive definition, as its value is based on the value of another factorial.

This is how our finished factorial program would look like:

#include <stdlib.h>

int

factorial (int n)

{

if (n == 0)

return 1;

return n * factorial (n - 1);

}

int

main (void)

{

printf ("5! = %d\n", factorial (5));

return 0;

}And the output of this program would be: 5! = 120

The sequence of operations that is performed in the evaluation of `factorial (3)' can be conceptualised as follows:

factorial (3) = 3 * factorial (2)

= 3 * 2 * factorial (1)

= 3 * 2 * 1 * factorial (0)

= 3 * 2 * 1 * 1

= 6Recursion vs Iteration

Any problem that can be solved recursively, can also be solved iteratively (non-recursively using loops), both iteration and recursion are based on a control structure: iteration uses a repetition structure, and recursion uses a selection structure. Both of them involve repetition: iteration explicitely uses a repetition structure and recursion achieves repetition through repeated function calls. Both of them involve a termination test: iteration terminates when the loop-continuation condition fails and recursion terminates when a base case is recognised, iteration with counter-controlled repetition and recursion each gradually approach termination, iteration keeps modifying a counter until it assumes a value that makes the loop-continuation condition fails and recursion keeps producing simpler versions of the original problem until the base case is reached.

Both iteration and recursion can occur infinitely, an infinite loop occurs with iteration if the loop-continuation test never becomes false and infinite recursion occurs if the recursion step does not reduce the problem each time in a manner that converges the base case.

A recursive approach is normally chosen in preference to an interative approach when the recursive one more naturally mirros the problem, as it results in a program that is easier to understand and debug.

Recursion pros and cons

Recursion sometimes offers the simplest solution to some programming problems.

Recursive functions can rapidly exhaust a computer's memory recourses as it repeatedly invokes the mechanism, and consequently the overhead, of function calls (it's expensive in both processor time and memory space). Each recursive calls causes another copy of the function (only the function's variables) to be created (this can consume a considerable amount of memory).

Avoid using recursion in performance situations.

Recursion can also be difficult to document and maintain by other programmers that are not familiar with recursion.

Tail Recursion

Tail recursion is the simplest form of recursion, the recursive call is at the end of the function, just before the return statement, it comes at the end and acts like a loop.

Tail recursive functions can be optimised by the compiler, since the recursive call is the last statement, there's nothing left to do in the current function, so saving the current function's stack frame is of no use.

This is an example of a tail-recursive function:

void

printf (int n)

{

if (n < 0)

return;

printf (n - 1);

}